One of my clearest early memories is of me sitting in my grandfather’s Lazy Boy in the pre-dawn gray light, listening to my grandmother talk on the phone. I was about five years old, living in Virginia at the time but visiting my grandparents in Texas for the summer. It was probably only five in the morning, but I never slept well when away from home, and I was always an early riser as a child anyway. So I had crawled out of bed and joined my grandmother in the great room — a combo living room, dining room, and kitchen. It seemed my grandmother was always awake — the first awake in the morning, the last to bed at night.

So, I sat curled up in my grandfather’s giant leather recliner. My grandmother was behind me shuffling around in the kitchen. Her feet were heavily calloused from working in rice fields in her teens and early twenties, and created a soft shushing sound against the linoleum floor. Her slightly high-pitched lilting voice washed over me like a wave. But I couldn’t understand a word she said on the phone.

She was speaking Japanese, which I have never yet learned. In fact, no one else in my family can speak Japanese at all. In her teens, my grandmother stopped speaking the language, and later she refused to teach any of her six children how to speak it. It was only years later, when I was born, and my great-grandmother had come twice from Japan to visit, that she began to speak it again.

Her refusal to speak her own language haunts me some days. She learned early that “different” is dangerous.

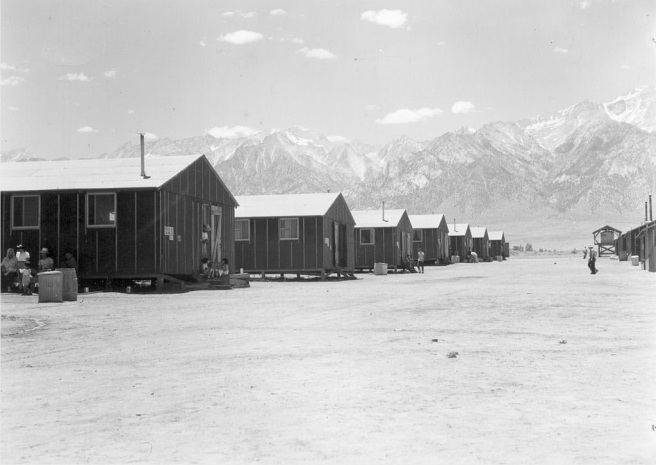

My grandmother was born in San Francisco, the first child of two Japanese immigrants who had come from Hiroshima to Hawaii (which was not yet a state, but its own kingdom still at the time), and then from Hawaii to California. The path of many Japanese families in the 20s, 30s, and 40s. In time, she would end up with ten brothers and sisters. And when she was ten years old, my grandmother and her entire family were locked away in Manzanar, one of the concentration camps the U.S. government built during World War Two to imprison Japanese-American citizens. By the time the war had ended, and her family was released, my grandmother had only five brothers and sisters. And her parents’ ancestral home, Hiroshima, had been bombed into oblivion.

Five of her uncles and cousins had fought for the U.S. during the war, members of the famous 442nd, despite the fact that their families — their sisters, their wives, their children — had been herded up like animals and left to rot in camps in the middle of the California, Arizona, and New Mexico deserts. Her parents returned to Hiroshima after the war. Meanwhile, my grandmother stayed in Los Angeles, went to school, worked as a seamstress, and was accepted into medical school at the age of sixteen. Sadly, she would never have the opportunity to complete her education, because her father developed cancer — mostly likely due to the radiation that still yet lingers in Hiroshima — and died. After that, my grandmother, the oldest child, was forced to quit school and work in rice fields in order to send money back to her mother and siblings.

So close to fulfilling the dream of all immigrants — a good education and successful career — and then her plans were ended. She married at the age of twenty; married my grandfather, a Marine and a Cajun from Baton Rouge, became a housewife, and gave birth to six children who would never learn her language because she did not want them to suffer the way she and her siblings had suffered. Because she wanted them to be as American, and therefore as safe, as they could possibly be.

As heart-breaking as this conclusion was, it seems to have worked. Her children, and their children, have been safe (relatively speaking anyway). All six children spent some time in the military, four years or six years — my mother staying the longest and making a career in the Marine Corps. And now, here I am, the first in my family to receive a Master’s degree or work toward a PhD, only the third to go to college at all, in some ways fulfilling the dream my grandmother had all those decades ago.

I am grateful for the chances I’ve had. There are few places in the world where a mixed race poor working-class family could make it as far as we have. But I can’t help but always be a little suspicious of our luck, and a little bitter about the chances my grandmother and all her brothers and sisters were denied. If I learned anything from my grandmother, it is that nothing is safe, and we must take nothing for granted. And some day I hope she’ll let me learn her language.

Signed,

Silent Sister